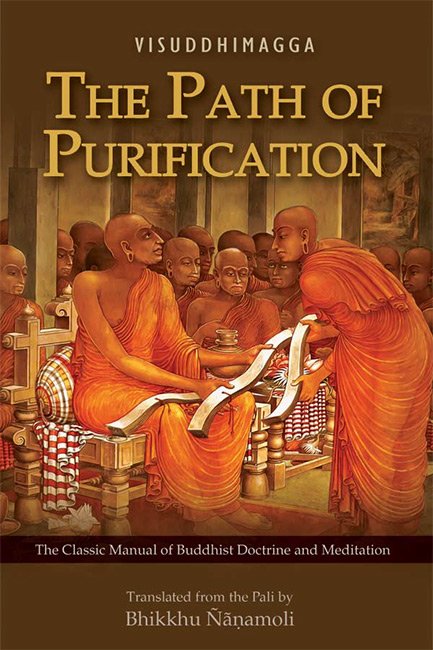

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes The First Jhana of the section The Earth Kasiṇa (Pathavī-kasiṇa-niddesa) of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

The First Jhāna

79. At this point, “Quite secluded from sense desires, secluded from unprofitable things he enters upon and dwells in the first jhāna, which is accompanied by applied and sustained thought with happiness and bliss born of seclusion” (Vibh 245), and so he has attained the first jhāna, which abandons five factors, possesses five factors, is good in three ways, possesses ten characteristics, and is of the earth kasiṇa.

80. Herein, quite secluded from sense desires means having secluded himself from, having become without, having gone away from, sense desires. Now, this word quite (eva) should be understood to have the meaning of absoluteness. Precisely because it has the meaning of absoluteness it shows how, on the actual occasion of entering upon and dwelling in the first jhāna, sense desires as well as being non-existent then are the first jhāna’s contrary opposite, and it also shows that the arrival takes place only (eva) through the letting go of sense desires. How?

81. When absoluteness is introduced thus, “quite secluded from sense desires,” what is expressed is this: sense desires are certainly incompatible with this jhāna; when they exist, it does not occur, just as when there is darkness, there is no lamplight; and it is only by letting go of them that it is reached, just as the further bank is reached only by letting go of the near bank. That is why absoluteness is introduced.

82. Here it might be asked: But why is this [word “quite”] mentioned only in the first phrase and not in the second? How is this, might he enter upon and dwell in the first jhāna even when not secluded from unprofitable things?—It should not be regarded in that way. It is mentioned in the first phrase as the escape from them; for this jhāna is the escape from sense desires since it surmounts the sense-desire element and since it is incompatible with greed for sense desires, according as it is said: “The escape from sense desires is this, that is to say, renunciation” (D III 275). But in the second phrase [140] the word eva should be adduced and taken as said, as in the passage, “Bhikkhus, only (eva) here is there an ascetic, here a second ascetic” (M I 63). For it is impossible to enter upon and dwell in jhāna unsecluded also from unprofitable things, in other words, the hindrances other than that [sense desire]. So this word must be read in both phrases thus: “Quite secluded from sense desires, quite secluded from unprofitable things.” And although the word “secluded” as a general term includes all kinds of seclusion, that is to say, seclusion by substitution of opposites, etc., and bodily seclusion, etc.,[1] still only the three, namely, bodily seclusion, mental seclusion, and seclusion by suppression (suspension) should be regarded here.

83. But this term “sense desires” should be regarded as including all kinds, that is to say, sense desires as object as given in the Niddesa in the passage beginning, “What are sense desires as object? They are agreeable visible objects …” (Nidd I 1), and the sense desires as defilement given there too and in the Vibhaṅga thus: “Zeal as sense desire (kāma), greed as sense desire, zeal and greed as sense desire, thinking as sense desire, greed as sense desire, thinking and greed as sense desire”[2] (Nidd I 2; Vibh 256). That being so, the words “quite secluded from sense desires” properly mean “quite secluded from sense desires as object,” and express bodily seclusion, while the words “secluded from unprofitable things” properly mean “secluded from sense desires as defilement or from all unprofitable things,” and express mental seclusion. And in this case giving up of pleasure in sense desires is indicated by the first since it only expresses seclusion from sense desires as object, while acquisition of pleasure in renunciation is indicated by the second since it expresses seclusion from sense desire as defilement.

84. And with sense desires as object and sense desires as defilement expressed in this way, it should also be recognized that the abandoning of the objective basis for defilement is indicated by the first of these two phrases and the abandoning of the [subjective] defilement by the second; also that the giving up of the cause of cupidity is indicated by the first and [the giving up of the cause] of stupidity by the second; also that the purification of one’s occupation is indicated by the first and the educating of one’s inclination by the second.

This, firstly, is the method here when the words from sense desires are treated as referring to sense desires as object.

85. But if they are treated as referring to sense desires as defilement, then it is simply just zeal for sense desires (kāmacchanda) in the various forms of zeal (chanda), greed (rāga), etc., that is intended as “sense desires” (kāma) (§83, 2nd quotation). [141] And although that [lust] is also included by [the word] “unprofitable,” it is nevertheless stated separately in the Vibhaṅga in the way beginning, “Herein, what are sense desires? Zeal as sense desire …” (Vibh 256) because of its incompatibility with jhāna. Or, alternatively, it is mentioned in the first phrase because it is sense desire as defilement and in the second phrase because it is included in the “unprofitable.” And because this [lust] has various forms, therefore “from sense desires” is said instead of “from sense desire.”

86. And although there may be unprofitableness in other states as well, nevertheless only the hindrances are mentioned subsequently in the Vibhaṅga thus, “Herein, what states are unprofitable? Lust …” (Vibh 256), etc., in order to show their opposition to, and incompatibility with, the jhāna factors. For the hindrances are the contrary opposites of the jhāna factors: what is meant is that the jhāna factors are incompatible with them, eliminate them, abolish them. And it is said accordingly in the Peṭaka (Peṭakopadesa): “Concentration is incompatible with lust, happiness with ill will, applied thought with stiffness and torpor, bliss with agitation and worry, and sustained thought with uncertainty” (not in Peṭakopadesa).

87. So in this case it should be understood that seclusion by suppression (suspension) of lust is indicated by the phrase quite secluded from sense desires, and seclusion by suppression (suspension) of [all] five hindrances by the phrase secluded from unprofitable things. But omitting repetitions, that of lust is indicated by the first and that of the remaining hindrances by the second. Similarly with the three unprofitable roots, that of greed, which has the five cords of sense desire (M I 85) as its province, is indicated by the first, and that of hate and delusion, which have as their respective provinces the various grounds for annoyance (A IV 408; V 150), etc., by the second. Or with the states consisting of the floods, etc., that of the flood of sense desires, of the bond of sense desires, of the canker of sense desires, of sense-desire clinging, of the bodily tie of covetousness, and of the fetter of greed for sense desires, is indicated by the first, and that of the remaining floods, bonds, cankers, clingings, ties, and fetters, is indicated by the second. Again, that of craving and of what is associated with craving is indicated by the first, and that of ignorance and of what is associated with ignorance is indicated by the second. Furthermore, that of the eight thoughtarisings associated with greed (XIV.90) is indicated by the first, and that of the remaining kinds of unprofitable thought-arisings is indicated by the second.

This, in the first place, is the explanation of the meaning of the words “quite secluded from sense desires, secluded from unprofitable things.”

88. So far the factors abandoned by the jhāna have been shown. And now, in order to show the factors associated with it, which is accompanied by applied and sustained thought is said. [142] Herein, applied thinking (vitakkana) is applied thought (vitakka); hitting upon, is what is meant.[3] It has the characteristic of directing the mind on to an object (mounting the mind on its object). Its function is to strike at and thresh—for the meditator is said, in virtue of it, to have the object struck at by applied thought, threshed by applied thought. It is manifested as the leading of the mind onto an object. Sustained thinking (vicaraṇa) is sustained thought (vicāra);continued sustainment (anusañcaraṇa), is what is meant. It has the characteristic of continued pressure on (occupation with) the object. Its function is to keep conascent [mental] states [occupied] with that. It is manifested as keeping consciousness anchored [on that object].

89. And, though sometimes not separate, applied thought is the first impact of the mind in the sense that it is both gross and inceptive, like the striking of a bell. Sustained thought is the act of keeping the mind anchored, in the sense that it is subtle with the individual essence of continued pressure, like the ringing of the bell. Applied thought intervenes, being the interference of consciousness at the time of first arousing [thought], like a bird’s spreading out its wings when about to soar into the air, and like a bee’s diving towards a lotus when it is minded to follow up the scent of it. The behaviour of sustained thought is quiet, being the near non-interference of consciousness, like the bird’s planing with outspread wings after soaring into the air, and like the bee’s buzzing above the lotus after it has dived towards it.

90. In the commentary to the Book of Twos[4] this is said: “Applied thought occurs as a state of directing the mind onto an object, like the movement of a large bird taking off into the air by engaging the air with both wings and forcing them downwards. For it causes absorption by being unified. Sustained thought occurs with the individual essence of continued pressure, like the bird’s movement when it is using (activating) its wings for the purpose of keeping hold on the air. For it keeps pressing the object[5]”. That fits in with the latter’s occurrence as anchoring. This difference of theirs becomes evident in the first and second jhānas [in the fivefold reckoning].

91. Furthermore, applied thought is like the hand that grips firmly and sustained thought is like the hand that rubs, when one grips a tarnished metal dish firmly with one hand and rubs it with powder and oil and a woollen pad with the other hand. Likewise, when a potter has spun his wheel with a stroke on the stick and is making a dish [143], his supporting hand is like applied thought and his hand that moves back and forth is like sustained thought. Likewise, when one is drawing a circle, the pin that stays fixed down in the centre is like applied thought, which directs onto the object, and the pin that revolves round it is like sustained thought, which continuously presses.

92. So this jhāna occurs together with this applied thought and this sustained thought and it is called, “accompanied by applied and sustained thought” as a tree is called “accompanied by flowers and fruits.” But in the Vibhaṅga the teaching is given in terms of a person[6] in the way beginning, “He is possessed, fully possessed, of this applied thought and this sustained thought” (Vibh 257). The meaning should be regarded in the same way there too.

93. Born of seclusion: here secludedness (vivitti) is seclusion (viveka); the meaning is, disappearance of hindrances. Or alternatively, it is secluded (vivitta), thus it is seclusion; the meaning is, the collection of states associated with the jhāna is secluded from hindrances. “Born of seclusion” is born of or in that kind of seclusion.

94. Happiness and bliss: it refreshes (pīnayati), thus it is happiness (pīti). It has the characteristic of endearing (sampiyāyanā). Its function is to refresh the body and the mind; or its function is to pervade (thrill with rapture). It is manifested as elation. But it is of five kinds as minor happiness, momentary happiness, showering happiness, uplifting happiness, and pervading (rapturous) happiness.

Herein, minor happiness is only able to raise the hairs on the body. Momentary happiness is like flashes of lightning at different moments. Showering happiness breaks over the body again and again like waves on the sea shore.

95. Uplifting happiness can be powerful enough to levitate the body and make it spring up into the air. For this was what happened to the Elder Mahā-Tissa, resident at Puṇṇavallika. He went to the shrine terrace on the evening of the full-moon day. Seeing the moonlight, he faced in the direction of the Great Shrine [at Anurādhapura], thinking, “At this very hour the four assemblies[7] are worshipping at the Great Shrine!” By means of objects formerly seen [there] he aroused uplifting happiness with the Enlightened One as object, and he rose into the air like a painted ball bounced off a plastered floor and alighted on the terrace of the Great Shrine.

96. And this was what happened to the daughter of a clan in the village of Vattakālaka near the Girikaṇḍaka Monastery when she sprang up into the air owing to strong uplifting happiness with the Enlightened One as object. As her parents were about to go to the monastery in the evening, it seems, in order to hear the Dhamma [144], they told her: “My dear, you are expecting a child; you cannot go out at an unsuitable time. We shall hear the Dhamma and gain merit for you.” So they went out. And though she wanted to go too, she could not well object to what they said. She stepped out of the house onto a balcony and stood looking at the Ākāsacetiya Shrine at Girikaṇḍaka lit by the moon. She saw the offering of lamps at the shrine, and the four communities as they circumambulated it to the right after making their offerings of flowers and perfumes; and she heard the sound of the massed recital by the Community of Bhikkhus. Then she thought: “How lucky they are to be able to go to the monastery and wander round such a shrine terrace and listen to such sweet preaching of Dhamma!” Seeing the shrine as a mound of pearls and arousing uplifting happiness, she sprang up into the air, and before her parents arrived she came down from the air into the shrine terrace, where she paid homage and stood listening to the Dhamma.

97. When her parents arrived, they asked her, “What road did you come by?” She said, “I came through the air, not by the road,” and when they told her, “My dear, those whose cankers are destroyed come through the air. But how did you come?” she replied: “As I was standing looking at the shrine in the moonlight a strong sense of happiness arose in me with the Enlightened One as its object. Then I knew no more whether I was standing or sitting, but only that I was springing up into the air with the sign that I had grasped, and I came to rest on this shrine terrace.”

So uplifting happiness can be powerful enough to levitate the body, make it spring up into the air.

98. But when pervading (rapturous) happiness arises, the whole body is completely pervaded, like a filled bladder, like a rock cavern invaded by a huge inundation.

99. Now, this fivefold happiness, when conceived and matured, perfects the twofold tranquillity, that is, bodily and mental tranquillity. When tranquillity is conceived and matured, it perfects the twofold bliss, that is, bodily and mental bliss. When bliss is conceived and matured, it perfects the threefold concentration, that is, momentary concentration, access concentration, and absorption concentration.

Of these, what is intended in this context by happiness is pervading happiness, which is the root of absorption and comes by growth into association with absorption. [145]

100. But as to the other word: pleasing (sukhana) is bliss (sukha). Or alternatively: it thoroughly (SUṭṭhu) devours (KHĀdati), consumes (KHAṇati),[8] bodily and mental affliction, thus it is bliss (sukha). It has gratifying as its characteristic. Its function is to intensify associated states. It is manifested as aid.

And wherever the two are associated, happiness is the contentedness at getting a desirable object, and bliss is the actual experiencing of it when got. Where there is happiness there is bliss (pleasure); but where there is bliss there is not necessarily happiness. Happiness is included in the formations aggregate; bliss is included in the feeling aggregate. If a man, exhausted[9] in a desert, saw or heard about a pond on the edge of a wood, he would have happiness; if he went into the wood’s shade and used the water, he would have bliss. And it should be understood that this is said because they are obvious on such occasions.

101. Accordingly, (a) this happiness and this bliss are of this jhāna, or in this jhāna; so in this way this jhāna is qualified by the words with happiness and bliss [and also born of seclusion]. Or alternatively: (b) the words happiness and bliss (pītisukhaṃ) can be taken as “the happiness and the bliss” independently, like “the Dhamma and the Discipline” (dhammavinaya), and so then it can be taken as seclusion-born happiness-and-bliss of this jhāna, or in this jhāna; so in this way it is the happiness and bliss [rather than the jhāna] that are born of seclusion. For just as the words “born of seclusion” can [as at (a)] be taken as qualifying the word “jhāna,” so too they can be taken here [as at (b)] as qualifying the expression “happiness and bliss,” and then that [total expression] is predicated of this [jhāna]. So it is also correct to call “happiness-and-bliss born-of-seclusion” a single expression. In the Vibhaṅga it is stated in the way beginning, “This bliss accompanied by this happiness” (Vibh 257). The meaning should be regarded in the same way there too.

102. First jhāna: this will be explained below (§119).

Enters upon (upasampajja): arrives at; reaches, is what is meant; or else, taking it as “makes enter” (upasampādayitvā), then producing, is what is meant. In the Vibhaṅga this is said: “‘Enters upon’: the gaining, the regaining, the reaching, the arrival at, the touching, the realizing of, the entering upon (upasampadā, the first jhāna” (Vibh 257), the meaning of which should be regarded in the same way.

103. And dwells in (viharati): by becoming possessed of jhāna of the kind described above through dwelling in a posture favourable to that [jhāna], he produces a posture, a procedure, a keeping, an enduring, a lasting, a behaviour, a dwelling, of the person. For this is said in the Vibhaṅga: “‘Dwells in’: poses, proceeds, keeps, endures, lasts, behaves, dwells; [146] hence ‘dwells’ is said” (Vibh 252).

104. Now, it was also said above which abandons five factors, possesses five factors (§79;cf. M I 294). Herein, the abandoning of the five factors should be understood as the abandoning of these five hindrances, namely, lust, ill will, stiffness and torpor, agitation and worry, and uncertainty; for no jhāna arises until these have been abandoned, and so they are called the factors of abandoning. For although other unprofitable things too are abandoned at the moment of jhāna, still only these are specifically obstructive to jhāna.

105. The mind affected through lust by greed for varied objective fields does not become concentrated on an object consisting in unity, or being overwhelmed by lust, it does not enter on the way to abandoning the sense-desire element. When pestered by ill will towards an object, it does not occur uninterruptedly. When overcome by stiffness and torpor, it is unwieldy. When seized by agitation and worry, it is unquiet and buzzes about. When stricken by uncertainty, it fails to mount the way to accomplish the attainment of jhāna. So it is these only that are called factors of abandoning because they are specifically obstructive to jhāna.

106. But applied thought directs the mind onto the object; sustained thought keeps it anchored there. Happiness produced by the success of the effort refreshes the mind whose effort has succeeded through not being distracted by those hindrances; and bliss intensifies it for the same reason. Then unification aided by this directing onto, this anchoring, this refreshing and this intensifying, evenly and rightly centres (III.3) the mind with its remaining associated states on the object consisting in unity. Consequently, possession of five factors should be understood as the arising of these five, namely, applied thought, sustained thought, happiness, bliss and unification of mind.

107. For it is when these are arisen that jhāna is said to be arisen, which is why they are called the five factors of possession. Therefore it should not be assumed that the jhāna is something other which possesses them. But just as “The army with the four factors” (Vin IV 104) and “Music with the five factors” (M-a II 300) and “The path with the eight factors (eightfold path)” are stated simply in terms of their factors, so this too [147] should be understood as stated simply in terms of its factors, when it is said to “have five factors” or “possess five factors.”

108. And while these five factors are present also at the moment of access and are stronger in access than in normal consciousness, they are still stronger here than in access and acquire the characteristic of the fine-material sphere. For applied thought arises here directing the mind on to the object in an extremely lucid manner, and sustained thought does so pressing the object very hard, and the happiness and bliss pervade the entire body. Hence it is said: “And there is nothing of his whole body not permeated by the happiness and bliss born of seclusion” (D I 73). And unification too arises in the complete contact with the object that the surface of a box’s lid has with the surface of its base. This is how they differ from the others.

109. Although unification of mind is not actually listed among these factors in the [summary] version [beginning] “which is accompanied by applied and sustained thought” (Vibh 245), nevertheless it is mentioned [later] in the Vibhaṅga as follows: “‘Jhāna’: it is applied thought, sustained thought, happiness, bliss, unification”(Vibh 257), and so it is a factor too; for the intention with which the Blessed One gave the summary is the same as that with which he gave the exposition that follows it.

110. Is good in three ways, possesses ten characteristics (§79): the goodness in three ways is in the beginning, middle, and end. The possession of the ten characteristics should be understood as the characteristics of the beginning, middle, and end, too. Here is the text:

111. “Of the first jhāna, purification of the way is the beginning, intensification of equanimity is the middle, and satisfaction is the end.

“‘Of the first jhāna, purification of the way is the beginning’: how many characteristics has the beginning? The beginning has three characteristics: the mind is purified of obstructions to that [jhāna]; because it is purified the mind makes way for the central [state of equilibrium, which is the] sign of serenity; because it has made way the mind enters into that state. And it is since the mind becomes purified of obstructions and, through being purified, makes way for the central [state of equilibrium, which is the] sign of serenity and, having made way, enters into that state, that the purification of the way is the beginning of the first jhāna. These are the three characteristics of the beginning. Hence it is said: ‘The first jhāna is good in the beginning which possesses three characteristics.’ [148]

112. “‘Of the first jhāna intensification of equanimity is the middle’: how many characteristics has the middle? The middle has three characteristics. He [now] looks on with equanimity at the mind that is purified; he looks on with equanimity at it as having made way for serenity; he looks on with equanimity at the appearance of unity.[10] And in that he [now] looks on with equanimity at the mind that is purified and looks on with equanimity at it as having made way for serenity and looks on with equanimity at the appearance of unity, that intensification of equanimity is the middle of the first jhāna. These are the three characteristics of the middle. Hence it is said: ‘The first jhāna is good in the middle which possesses three characteristics.’

113. “‘Of the first jhāna satisfaction is the end’: how many characteristics has the end? The end has four characteristics. The satisfaction in the sense that there was non-excess of any of the states arisen therein, and the satisfaction in the sense that the faculties had a single function, and the satisfaction in the sense that the appropriate energy was effective, and the satisfaction in the sense of repetition, are the satisfaction in the end of the first jhāna. These are the four characteristics of the end. Hence it is said: ‘The first jhāna is good in the end which possesses four characteristics’” (Paṭis I 167–68).

114. Herein, purification of the way is access together with its concomitants. Intensification of equanimity is absorption. Satisfaction is reviewing. So some comment.[11] But it is said in the text, “The mind arrived at unity enters into purification of the way, is intensified in equanimity, and is satisfied by knowledge” (Paṭis I 167), and therefore it is from the standpoint within actual absorption that purification of the way firstly should be understood as the approach, with intensification of equanimity as the function of equanimity consisting in specific neutrality, and satisfaction as the manifestation of clarifying knowledge’s function in accomplishing non-excess of states. How?

115. Firstly, in a cycle [of consciousness] in which absorption arises the mind becomes purified from the group of defilements called hindrances that are an obstruction to jhāna. Being devoid of obstruction because it has been purified, it makes way for the central [state of equilibrium, which is the] sign of serenity. Now, it is the absorption concentration itself occurring evenly that is called the sign of serenity. But the consciousness immediately before that [149] reaches that state by way of change in a single continuity (cf. XXII.1–6), and so it is said that it makes way for the central [state of equilibrium, which is the] sign of serenity. And it is said that it enters into that state by approaching it through having made way for it. That is why in the first place purification of the way, while referring to aspects existing in the preceding consciousness, should nevertheless be understood as the approach at the moment of the first jhāna’s actual arising.

116. Secondly, when he has more interest in purifying, since there is no need to re-purify what has already been purified thus, it is said that he looks on with equanimity at the mind that is purified. And when he has no more interest in concentrating again what has already made way for serenity by arriving at the state of serenity, it is said that he looks on with equanimity at it as having made way for serenity. And when he has no more interest in again causing appearance of unity in what has already appeared as unity through abandonment of its association with defilement in making way for serenity, it is said that he looks on with equanimity at the appearance of unity. That is why intensification of equanimity should be understood as the function of equanimity that consists in specific neutrality.

117. And lastly, when equanimity was thus intensified, the states called concentration and understanding produced there, occurred coupled together without either one exceeding the other. And also the [five] faculties beginning with faith occurred with the single function (taste) of deliverance owing to deliverance from the various defilements. And also the energy appropriate to that, which was favourable to their state of non-excess and single function, was effective. And also its repetition occurs at that moment.[12] Now, all these [four] aspects are only produced because it is after seeing with knowledge the various dangers in defilement and advantages in cleansing that satisfiedness, purifiedness and clarifiedness ensue accordingly. That is the reason why it was said that satisfaction should be understood as the manifestation of clarifying knowledge’s function in accomplishing non-excess, etc., of states (§114).

118. Herein, satisfaction as a function of knowledge is called “the end” since the knowledge is evident as due to onlooking equanimity, according as it is said: “He looks on with complete equanimity at the mind thus exerted; then the understanding faculty is outstanding as understanding due to equanimity. Owing to equanimity the mind is liberated from the many sorts of defilements; then the understanding faculty is outstanding as understanding due to liberation. Because of being liberated these states come to have a single function; then [the understanding faculty is outstanding as understanding due to] development in the sense of the single function”[13] (Paṭis II 25).

119. Now, as to the words and so he has attained the first jhāna … of the earth kasiṇa (§79): Here it is first because it starts a numerical series;[150] also it is first because it arises first. It is called jhāna because of lighting (upanijjhāna) the object and because of burning up (jhāpana) opposition (Paṭis I 49). The disk of earth is called earth kasiṇa (paṭhavīkasiṇa—lit. “earth universal”) in the sense of entirety,[14] and the sign acquired with that as its support and also the jhāna acquired in the earth-kasiṇa sign are so called too. So that jhāna should be understood as of the earth kasiṇa in this sense, with reference to which it was said above “and so he has attained to the first jhāna … of the earth kasiṇa.”

120. When it has been attained in this way, the mode of its attainment must be discerned by the meditator as if he were a hair-splitter or a cook. For when a very skilful archer, who is working to split a hair, actually splits the hair on one occasion, he discerns the modes of the position of his feet, the bow, the bowstring, and the arrow thus: “I split the hair as I stood thus, with the bow thus, the bowstring thus, the arrow thus.” From then on he recaptures those same modes and repeats the splitting of the hair without fail. So too the meditator must discern such modes as that of suitable food, etc., thus: “I attained this after eating this food, attending on such a person, in such a lodging, in this posture at this time.” In this way, when that [absorption] is lost, he will be able to recapture those modes and renew the absorption, or while familiarizing himself with it he will be able to repeat that absorption again and again.

121. And just as when a skilled cook is serving his employer, he notices whatever he chooses to eat and from then on brings only that sort and so obtains a reward, so too this meditator discerns such modes as that of the food, etc., at the time of the attaining, and he recaptures them and re-obtains absorption each time it is lost. So he must discern the modes as a hair-splitter or a cook does.

122. And this has been said by the Blessed One: “Bhikkhus, suppose a wise, clever, skilful cook set various kinds of sauces before a king or a king’s minister, such as sour, bitter, sharp, [151] sweet, peppery and unpeppery, salty and unsalty sauces; then the wise, clever, skilful cook learned his master’s sign thus ‘today this sauce pleased my master’ or ‘he held out his hand for this one’ or ‘he took a lot of this one’ or ‘he praised this one’ or ‘today the sour kind pleased my master’ or ‘he held out his hand for the sour kind’ or ‘he took a lot of the sour kind’ or ‘he praised the sour kind’ … or ‘he praised the unsalty kind’; then the wise, clever, skilful cook is rewarded with clothing and wages and presents. Why is that? Because that wise, clever, skilful cook learned his master’s sign in this way. So too, bhikkhus, here a wise, clever, skilful bhikkhu dwells contemplating the body as a body … He dwells contemplating feelings as feelings … consciousness as consciousness … mental objects as mental objects, ardent, fully aware and mindful, having put away covetousness and grief for the world. As he dwells contemplating mental objects as mental objects, his mind becomes concentrated, his defilements are abandoned. He learns the sign of that. Then that wise, clever, skilful bhikkhu is rewarded with a happy abiding here and now, he is rewarded with mindfulness and full awareness. Why is that? Because that wise, clever, skilful bhikkhu learned his consciousness’s sign” (S V 151–52).

123. And when he recaptures those modes by apprehending the sign, he just succeeds in reaching absorption, but not in making it last. It lasts when it is absolutely purified from states that obstruct concentration.

124. When a bhikkhu enters upon a jhāna without [first] completely suppressing lust by reviewing the dangers in sense desires, etc., and without [first] completely tranquillizing bodily irritability[15] by tranquillizing the body, and without [first] completely removing stiffness and torpor by bringing to mind the elements of initiative, etc., (§55), and without [first] completely abolishing agitation and worry by bringing to mind the sign of serenity, etc., [152] and without [first] completely purifying his mind of other states that obstruct concentration, then that bhikkhu soon comes out of that jhāna again, like a bee that has gone into an unpurified hive, like a king who has gone into an unclean park.

125. But when he enters upon a jhāna after [first] completely purifying his mind of states that obstruct concentration, then he remains in the attainment even for a whole day, like a bee that has gone into a completely purified hive, like a king who has gone into a perfectly clean park. Hence the Ancients said:

“So let him dispel any sensual lust, and resentment,

Agitation as well, and then torpor, and doubt as the fifth;

There let him find joy with a heart that is glad in seclusion,

Like a king in a garden where all and each corner is clean.”

126. So if he wants to remain long in the jhāna, he must enter upon it after [first] purifying his mind from obstructive states.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The five (see e.g. Paṭis II 220; M-a I 85) are suppression (by concentration), substitution of opposites (by insight), cutting off (by the path), tranquillization (by fruition), and escape (as Nibbāna); cf. five kinds of deliverance (e.g. M-a IV 168). The three (see e.g. Nidd I 26; M-a II 143) are bodily seclusion (retreat), mental seclusion (jhāna), and seclusion from the substance or circumstances of becoming (Nibbāna).

[2]:

Here saṅkappa (“thinking”) has the meaning of “hankering.” Chanda, kāma and rāga and their combinations need sorting out. Chanda (zeal, desire) is much used, neutral in colour, good or bad according to context and glossed by “desire to act”; technically also one of the four roads to power and four predominances. Kāma (sense desire, sensuality) loosely represents enjoyment of the five sense pleasures (e.g. sense-desire sphere). More narrowly it refers to sexual enjoyment (third of the Five Precepts). Distinguished as subjective desire (defilement) and objective things that arouse it (Nidd I 1; cf. Ch. XIV, n.36). The figure “five cords of sense desire” signifies simply these desires with the five sense objects that attract them. Rāga (greed) is the general term for desire in its bad sense and identical with lobha, which latter, however, appears technically as one of the three root-causes of unprofitable action. Rāga is renderable also by “lust” in its general sense. Kāmacchanda (lust): a technical term for the first of the five hindrances. Chanda-rāga (zeal and greed) and kāma-rāga (greed for sense desires) have no technical use.

[3]:

Ūhana—“hitting upon”: possibly connected with ūhanati (to disturb—see M I 243; II 193). Obviously connected here with the meaning of āhananapariyāhanana (“striking and threshing”) in the next line. For the similes that follow here, see Peṭ 142.

[4]:

Of the Aṅguttara Nikāya? [The original could not be traced anywhere in the Tipiṭaka, Aṭṭhakathā, and other texts contained in the digitalised Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana edition of the Vipassana Research Institute. Dhs-a 114 quotes the same passage, but gives the source as aṭṭhakathāyaṃ, “in the commentary.” BPS ed.]

[5]:

These two sentences, “So hi ekaggo hutvā appeti” and “So hi ārammaṇaṃ anumajjati,” are not in Be and Ae.

[6]:

Puggalādhiṭṭhāna—“in terms of a person”; a technical commentarial term for one of the ways of presenting a subject. They are dhammā-desanā (discourse about principles), and puggala-desanā (discourse about persons), both of which may be treated either as dhammādhiṭṭhāna (in terms of principles) or puggalādhiṭṭhāna (in terms of persons). See M-a I 24.

[7]:

The four assemblies (parisā) are the bhikkhus, bhikkhunīs, laymen followers and laywomen followers.

[8]:

For this word play see also XVII.48. Khaṇati is only given in normal meaning of “to dig” in PED. There seems to be some confusion of meaning with khayati (to destroy) here, perhaps suggested by khādati (to eat). This suggests a rendering here and in Ch. XVII of “to consume” which makes sense. Glossed by avadāriyati, to break or dig: not in PED. See CPD “avadārana.”

[9]:

Kantāra-khinna—“exhausted in a desert”; khinna is not in PED.

[10]:

Four unities (ekatta) are given in the preceding paragraph of the same Paṭisambhidā ref.: “The unity consisting in the appearance of relinquishment in the act of giving, which is found in those resolved upon generosity (giving up); the unity consisting in the appearance of the sign of serenity, which is found in those who devote themselves to the higher consciousness; the unity consisting in the appearance of the characteristic of fall, which is found in those with insight;the unity consisting in the appearance of cessation, which is found in noble persons” (Paṭis I 167). The second is meant here.

[11]:

“The inmates of the Abhayagiri Monastery in Anurādhapura” (Vism-mhṭ 144).

[12]:

“‘Its’: of that jhāna consciousness. ‘At that moment’: at the moment of dissolution; for when the moment of arising is past, repetition occurs starting with the moment of presence” (Vism-mhṭ 145). A curious argument; see §182.

[13]:

The quotation is incomplete and the end should read, “… ekarasaṭṭhena bhāvanāvasena paññāvasena paññindriyaṃ adhimattaṃ hoti.”

[14]:

“In the sense of the jhāna’s entire object. It is not made its partial object” (Vism-mhṭ 147).

[15]:

Kāya-duṭṭhulla—“bodily irritability”: explained here as “bodily disturbance (daratha), excitement of the body (kāya-sāraddhatā)” by Vism-mhṭ (p.148); here it represents the hindrance of ill will; cf. M III 151, 159, where commented on as kāyālasiya—“bodily inertia” (M-a IV 202, 208). PED, only gives meaning of “wicked, lewd” for duṭṭhulla, for which meaning see e.g. A I 88, Vin-a 528; cf. IX.69.