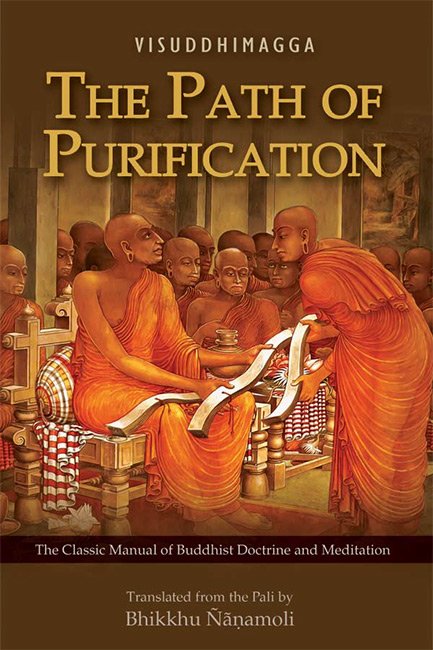

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

The English translation of the Visuddhimagga written by Buddhaghosa in the 5th Century. It contains the essence of the the teachings found in the Pali Tripitaka and represents, as a whole, an exhaustive meditation manual. The work consists of the three parts—1) Virtue (Sila), 2) Concentration (Samadhi) and 3) Understanding (Panna) covering twenty-t...

Trends in the Development of Theravāda Doctrine

The doctrines (Dhamma) of the Theravāda Pali tradition can be conveniently traced in three main layers. (1) The first of these contains the main books of the Pali Sutta Piṭakas. (2) The second is the Abhidhamma Piṭaka, notably the closely related books, the Dhammasaṅgaṇī, Vibhaṅga, Paṭṭhāna. (3) The third is the system which the author of the Visuddhimagga completed, or found completed, and which he set himself to edit and translate back into Pali (some further minor developments took place subsequently, particularly with the 12th century (?) Abhidhammatthasaṅgaha, but they are outside the present scope). The point at issue here is not the muchdebated historical question of how far the Abhidhamma books (leaving aside the Kathāvatthu) were contemporary with the Vinaya and Suttas, but rather what discernible direction they show in evolution of thought.

(1) The Suttas being taken as the original exposition of the Buddha’s teaching, (2) the Abhidhamma Piṭaka itself appears as a highly technical and specialized systematization, or complementary set of modifications built upon that. Its upon that. Its immediate purpose is, one may say, to describe and pin-point mental constituents and characteristics and relate them to their material basis and to each other (with the secondary object, perhaps, of providing an efficient defence in disputes with heretics and exponents of outsiders’ doctrines). Its ultimate purpose is to furnish additional techniques for getting rid of unjustified assumptions that favour clinging and so obstruct the attainment of the extinction of clinging. Various instruments have been forged in it for sorting and re-sorting experience expressed as dhammas (see Ch. VII, n.1). These instruments are new to the Suttas, though partly traceable to them. The principal instruments peculiar to it are three: (a) the strict treatment of experience (or the knowable and knowledge, using the words in their widest possible sense) in terms of momentary cognizable states (dhamma) and the definition of these states, which is done in the Dhammasaṅgaṇī and Vibhaṅga; (b) the creation of a”schedule” (mātikā) consisting of a set of triple (tika) and double (duka) classifications for sorting these states; and (c) the enumeration of twenty-four kinds of conditioning relations (paccaya), which is done in the Paṭṭhāna. The states as defined are thus, as it were, momentary “stills”;the structure of relations combines the stills into continuities; the schedule classifications indicate the direction of the continuities.

The three Abhidhamma books already mentioned are the essential basis for what later came to be called the “Abhidhamma method”: together they form an integral whole. The other four books, which may be said to support them in various technical fields, need not be discussed here. This, then, is a bare outline of what is in fact an enormous maze with many unexplored side-turnings.

(3) The system found in the Commentaries has moved on (perhaps slightly diverged) from the strict Abhidhamma Piṭaka standpoint. The Suttas offered descriptions of discovery; the Abhidhamma map-making; but emphasis now is not on discovery, or even on mapping, so much as on consolidating, filling in and explaining. The material is worked over for consistency. Among the principal new developments here are these. The “cognitive series” (citta-vīthi) in the occurrence of the conscious process is organized (see Ch. IV, n.13 and Table V) and completed, and its association with three different kinds of kamma is laid down. The term sabhāva (“individual essence,” “own-being” or “it-ness,” see Ch. VII, n.68) is introduced to explain the key word dhamma, thereby submitting that term to ontological criticism, while the samaya (“event” or “occasion”) of the Dhammasaṅgaṇī is now termed a khaṇa (“moment”), thus shifting the weight and balance a little in the treatment of time. Then there is the specific ascription of the three “instants” (khaṇa, too) of arising, presence and dissolution (uppāda-ṭṭhiti-bhaṅga) to each “moment” (khaṇa), one “material moment” being calculated to last as long as sixteen “mental moments” (XX.24; Dhs-a 60).[1] New to the Piṭakas are also the rather unwieldy enumeration of concepts (paññatti, see Ch. VIII, n.11), and the handy defining-formula of word-meaning, characteristic, function, manifestation, and proximate cause (locus); also many minor instances such as the substitution of the specific “heart-basis” for the Paṭṭhāna’s “material basis of mind,” the conception of “material octads,” etc., the detailed descriptions of the thirty-two parts of the body instead of the bare enumeration of the names in the Suttas (thirty-one in the four Nikāyas and thirty-two in the Khuddakapāṭha and the Paṭisambhidāmagga), and many more. And the word paramattha acquires a new and slightly altered currency. The question of how much this process of development owes to the post-Mauryan evolution of Sanskrit thought on the Indian mainland (either through assimilation or opposition) still remains to be explored, like so many others in this field. The object of this sketch is only to point to a few landmarks.