The Dawn of the Dhamma

Illuminations from the Buddha’s First Discourse

by Sucitto Bhikkhu | 76,370 words

Dedication: May all beings live happily, free from fear, and may all share in the blessings springing from the good that has been done....

Chapter 12 - Cultivation

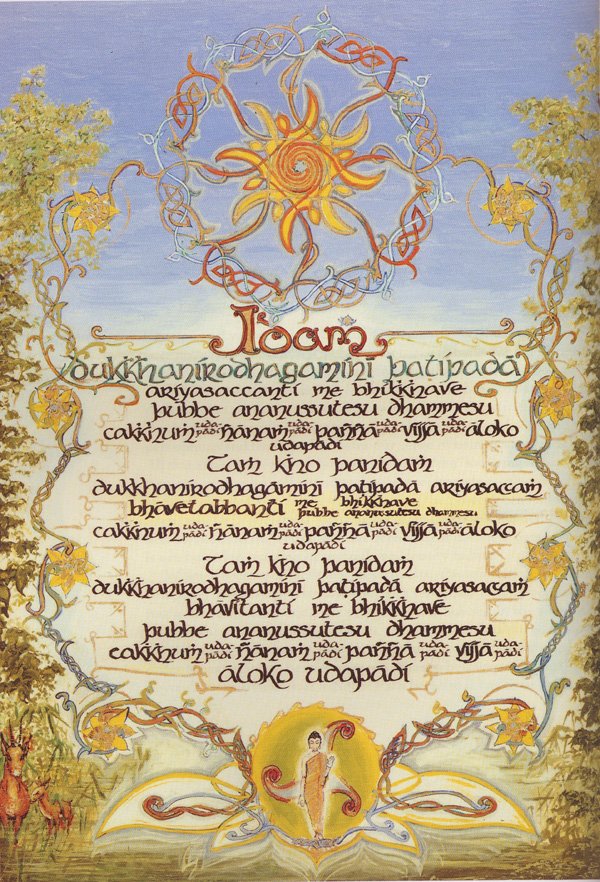

Idam dukkhanirodhagamini patipada …

Idam dukkhanirodhagamini patipada …

cakkhum udapadi nanam udapadi panna udapadi vijja udapadi aloko udapadi.

There is this Noble Truth of the Path leading to the Cessation of Suffering: …

This Noble Truth must be penetrated to by cultivating the Path: …

This Noble Truth has been penetrated to by cultivating the Path:

such was the vision, insight, wisdom, knowing and light that arose in me

about things not heard before.

This illustration shows a more dramatic change of style. Cessation is only the beginning; it should not be taken as a final deliverance. Having insights and then making too much of them can be an obstacle. In a moment, a great sense of realization may dawn and the mind can become very clear and peaceful. That may occur for a few minutes or even days, sometimes without practicing anything at all. There is the cessation. Some people still try to understand the meaning of a mystical experience of oneness that they had a decade ago. In a sense, it has subsequently spoiled their practice because they continue to remember that experience, and wish to repeat it again; or wonder whether it was really valid and where it went; and are unable to start afresh.

Sometimes people turn up at the monastery claiming to be Arahants (enlightened ones) and Bodhisattvas. The Arahants are difficult enough, they don"t want to fit into the routines and help out and they expect special treatment; but the Bodhisattvas are even worse, because they feel obliged to tell you how you"ve got it all wrong, and want to set up a teaching program. We had a Bodhisattva at Chithurst Monastery once but he couldn"t tolerate anything cooked in a teflon coated pan or any processed foods like white sugar or white rice, so he left.

Not everyone becomes so deluded, but people do have valid insights into not self and experiences of cessation that get distorted. It"s easy to get attached to insights, and to assume that you have become something. I recall in the early years of my practice having what seemed to me to be realizations of Truth and then the mind going on about them incessantly; sometimes it would take days for the mind to clear and relate to the here and now. I was so full of these great insights that I would get lost in thoughts and mental states and forget to clean my hut. Sometimes I"d feel that the experience of cessation or insight was just a fantasy but it was not necessarily the case. The problem was either taking cessation as self, or thinking one doesn"t have a self, or sundry permutations on this theme. As the Buddha put it:

This is how he attends unwisely: "Was I in the past! Was I not in the past? How was I in the past? Having been, what was I in the past?" (And similar patterns for present and future) … one of six kinds of view arises in him: the view "self exists for me" … or the view "no self exists for me" … "I perceive self with self" … "I perceive not self with self" … "I perceive self with not self." "It is this my self that speaks and feels, and that experiences here or there the ripening of good and bad actions … "

(Sabbasava Sutta; Majjhima Nikaya, 2)

As the last of the above views points out, the self view affects our activities, motivation and sense of achievement. It becomes extremely helpful, then, to live in a way that constantly asks something of you and trains you to relate to the here and now without self consciousness. It is equally helpful to see the whole process of life as one of not gaining anything, even liberation. Then that whole goal orientated way of thinking is discouraged. This, in a nutshell, is the practice of sustaining insights and letting go: the cultivation of the Fourth Noble Truth.

Insight into this Truth gives rise to Path Knowledge: knowing there is a Way rather than having a one off experience that becomes something personal and part of one"s self identity. Put into a proper perspective, the experience of cessation brings about a greater willingness to work within the world of conventional appearance, limitation, restrictions, things going wrong, things going right and so on. The Awakened mind sees all that dispassionately. Knowing there"s nothing to be liberated from except ignorance gives much scope for living insightfully.

This is how he attends wisely: "This is suffering," and "this is the origin of suffering," and " this is the cessation of suffering," and " this is the way leading to the cessation of suffering."

(Sabbasava Sutta)

In this picture, the upper lines that before were a cage have now turned inside out to form what is reminiscent of a sun, and also of a dance. This reminds me of the image of old fashioned dances where people formed circles with interlocked arms as seen from above. Along the sides, flowers again … eight of them in a flowing motif that is symbolic of the Eightfold Path. Down at the bottom is the Buddha, walking with the mudra of teaching in the world which was explained in the earlier frame on the Eightfold Path. Behind him is a triple armed figure that is a symbol of virtue, meditation and wisdom: the threefold aspect of the Path. All around are animals, plants—all that is begotten, born and dies—and it is through this world that the Buddha is walking in a serene way.

The Buddha described his own experience of fully Awakening in a particular way. It wasn"t just a momentary flash but a thorough review of the way the mind works, and, with each realization, the Buddha later commented: “But I allowed no pleasant feeling that arose in me to gain power over my mind.” The night under the Bodhi tree culminated in the realizations of the Four Noble Truths as well as the insight into the origin, cessation and Path leading to the cessation of the asava. Asava, which I have previously translated as “un knowing in action,” literally means “outflow.” The implication of the word suggests that, like a leak in a dam, it has the nature of creating further and more damaging outflows. Scholars" minds have strained to find a suitable equivalent in English to fully convey its meaning. The archaic “cankers” doesn"t mean very much nowadays and the relatively inactive sounding “taints” is quite common. Perhaps with further explanation, “outflows” will be the most useful term.

In this context, the Buddha described three outflows—three ways in which the mind rushes out in avalanche mode. These may be listed as: the outflow of sensuality or belief in the sensory “description” of reality, the outflow of becoming and the outflow of ignorance. The mind rushes into those modes of perceptual activity the way that water heads towards the sea down a gradient. Although there is volition, no conscious effort is necessary; because of this, by and large the outflows go unnoticed. Those who have no interest in Awakening will generally find themselves not questioning the veracity of the responses and perceptions that their sense faculties make with objects. Such is the power of the sensory outflow (kamasava).

Despite the changing and unsatisfying nature of sensory experiences, we find ourselves falling in love with new and refined ones. Exquisite states of mind bowl us over in the same way that glamorous movie stars used to. As in the case of the “Arahant” and “Bodhisattva” above, and in my own experience, interest in mental stimulation is one of the causes for grasping at insight. One can become quite intoxicated with thoughts or with the mental feeling of bliss or confidence that may come with insight. Spiritual adepts can become skilled at producing and even radiating such feelings. They may even be convinced from the refinement of the feelings that they have realized enlightenment. But when the outflow of sensuality is still active and one is moved by feelings, refined or otherwise, what one is experiencing is something other than the freedom of enlightenment.

Becoming is a powerful instinct that has already been explained. In its latent form as an outflow, it gives rise to the mood that looks for, or dreads, results instead of appreciating the present. So we are never able to appreciate the quality of our efforts or our stillness. This is not to suggest that we should be inactive, but that our activity can be appreciated for its goodness of intention and the skillfulness of its enactment, rather than be dogged by the nagging Furies of targeted goals. It is important to understand that this “outflowing” energy to get ahead and make things the way we want them to be is by no means all that we have access to. It is quite normal for people to apply themselves to a task for its own sake without the compulsion to become something or any hope for reward; we call it pure love or devotion.

Another more helpful recollection for our active side, is of the spirit of play. This avoids the pitfall of emotional attachment. Play can employ a lot of energy, concentration and mindfulness. It doesn"t have to be inane or fatuous. Drama itself arose out of a religious enactment, and came to represent archetypes and models of human behavior that would have an instructive quality. Similarly, art and poetry were originally sacred “play,” sometimes bringing forth the finest qualities that a person had in order to portray aspects of the human situation. The spiritual path is play in a like fashion—an enactment of the highest values, of the faculties of Wakefulness. In this, becoming something is completely irrelevant; one doesn"t believe that one is “enlightened,” nor that one is not. The self view is not being engaged. And the spiritual path is the supreme play because the script and the stage, or the raw materials, are our lives. Play is also adventurous and challenging and the personal fulfillment is dependent on the balance between commitment and dispassion. Then there is the necessary energy and the application without the burden of self consciousness: the self has been consumed in the purity of the action.

When we use the insight into play, the plot and the scenario of our activity are not crucial—it"s how we act within them that is important. Bringing the stage into the theater of the mind, we can develop skill in working with thoughts and feelings, activity, calm or confusion. This is liberating. Living in the present does not mean to consider nothing other than the tip of the nose, but that we are able to know plans about the future and memories as arising now, and having only a notional, “penciled in” existence. Do we find ourselves panicking or procrastinating? Failures and successes can be appraised and learnt from rather than stored up in memory. This is why, in Dhamma practice, the reference is to “skillful” and “unskillful” rather than “good” and “bad.”

The key problem again is ignorance, un knowing. This is the third outflow, requiring no conscious effort and no attention. Ignorance is the view of a mind that has not been matured by insights into the Four Noble Truths. For example, notice how surprised we are, and sometimes even shocked, that things go wrong, that there are misunderstandings, that pleasant relationships come to an end. Yet that is always the way it is. Why do we assume otherwise? Because of this outflow, this irrational assumption. This is ignorance, the refusal to develop a mature response to dukkha. As we have seen, the shock of dukkha triggers off defense mechanisms in the psyche—the desire to have and to hold on. From that is inferred an identity in terms of the five khandhas. This is what supports all the difficulties of life. Attachment to the five khandhas sets up a self opposed to dukkha and blocks the insight that could transcend dukkha. In that way, this outflow embeds dukkha in the psyche where it is ignored and left to foster and stimulate further outflows. Hence the enormous emphasis, as in the Satipatthana teachings, on applying clear “knowing,” knowing even greed, fear and doubt in an impartial way. That knowing has no self interest yet uses the mind keenly and without distraction. We replace, in a moment by moment way, ignorance with knowing.

The Way of cultivation is described in terms of an Eightfold Path. Throughout his teaching career, the Buddha gave many methods and elucidated numerous factors that would support Awakening. But in this Dhamma tour of the Eightfold Path, our scope is limited to guidelines of action, meditation and developing an understanding that is selfless. Cultivating these in terms of daily life requires a dynamic and on going teaching—ideally with reference to a trusted spiritual friend. The painting attempts to convey this as the way to a joyous life. Although the encouragement to sustain “knowing” as the principle for Awakening may sound ineffective and the reflections on sense restraint may appear quite chilling, a mind that does not flow out into proliferation and grasping at what is ephemeral is both glorious—and normal.

They do not repent over the past, nor do they brood over the future; they abide in the present: therefore they are radiant.

(Samyutta Nikaya: [I], Devas, Reed, 10)

The Buddha and his enlightened disciples, who had realized the cessation of dukkha, impressed people by their serene countenance: “cheerful, clearly rejoicing, with minds like the wild deer.” They did not drag themselves along in life, faded out and fed up with everything. It could not be that way: as you begin to see how suffering is compounded, you know that the cessation of suffering could only be realized by a sharp and agile mind and a gentle, patient heart. When the mind is liberated from craving and stops trying to set things up for oneself, then it radiates compassion, kindness, serenity and joy at the well being of others. The fire of desire has become a light radiance rather than a consuming flame. This is the natural mind—the way we act when we are not confused or distracted; when we are truly at ease, our inclination is to be loving and wise.